Lifted directly from my Moleskine®

Click edit button to change this text.

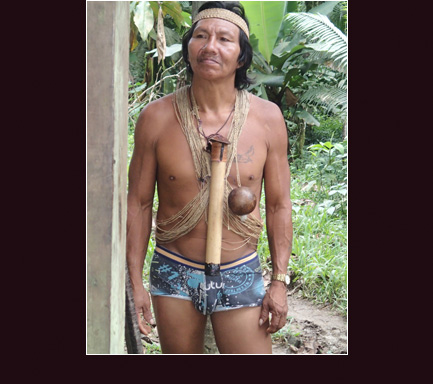

Five Days With The Huaorani

Huaorani consider themselves to be the bravest people in the Amazon. Through uncountable millennia they have defended their piece of the Oriente rainforest by killing everyone and anyone who they come across who was not Huaorani. Their spears were left in the bodies of the trespassers to ensure that their message was clear. The great expanse of the Aztec civilization avoided them and the Spanish empire dared not encroach on their part of the Amazon. Not even The Liberator, Simon Bolivar, would take his indefatigable troops into the Huaorani’s small piece of Ecuador. Today they stand up against a foe that they know will destroy the rainforest and put an end to their way of life: Big Oil. At the time that I was born, no one in the world who knew how to read or write was even aware that the Huaorani existed. By the time that I die they will be extinct. That is why we had to go.

What struck me immediately was that the jungle is not the scary place I had imagined. It is the Garden of Eden—the most bio-diverse place on the planet. There was a plethora of insects but they were not swarming in your face all the time. You had to be ever vigilant for snakes, scorpions, and other dangers beneath your feet. If you stumbled on a trail you did not reach out for a branch to steady yourself; it may have toxic stickers or the dreaded Conga ants that could paralyze your entire arm with one painful bite. You just let yourself fall to the ground; or better yet, you learned to walk more thoughtfully down the jungle path. It was wet and muddy.

What struck me immediately was that the jungle is not the scary place I had imagined. It is the Garden of Eden—the most bio-diverse place on the planet. There was a plethora of insects but they were not swarming in your face all the time. You had to be ever vigilant for snakes, scorpions, and other dangers beneath your feet. If you stumbled on a trail you did not reach out for a branch to steady yourself; it may have toxic stickers or the dreaded Conga ants that could paralyze your entire arm with one painful bite. You just let yourself fall to the ground; or better yet, you learned to walk more thoughtfully down the jungle path. It was wet and muddy.

The humidity could reach 100% but we were shaded and never far from the cool, flowing waters of the Shiripuno River. The jungle, I learned, could create its own rain shower when the evaporation of moisture from the understory was trapped under the broadleaves of the higher canopy.

Fa’a Samoa

It is awfully difficult for a barefoot school boy to pay attention to his lessons with the Pacific Ocean pounding on the beach just beyond the playground of Mokapu Elementary School. Even with less than half of my attention in the classroom I do remember Miss Wahineaukai teaching us, in her Pigeon-English, about the first Polynesians to settled in the Hawai’ian islands such a long time ago. With no compass or maps, with no written tradition in their culture, they sailed into the tiny island chain—the most remote body of land in the planet—after months in open canoes. Luck, I imagined: like seeds blown from a dandelion, a few found fertile ground but most of them perished at sea. The words of that Miss Wahineaukai that stayed with me through my entire life were “the wayfinders who guided these boats were high priest who had been given the vision and talked to the Gods of the sea. All of the strong kanes who manned the paddles placed their absolute faith and obedience in the wayfinder.”

Yeah! I got that. The only way that I would get in an open canoe and paddle out into the endless ocean for months on end, where I was probably going to die, would be if I had a delusional faith in the man at the helm. These Polynesian dudes were crazy—or driven by something that I had yet to understand, something in the seductive call of the Pacific Ocean.

Samoa is the heartland of Polynesia. It was from the Samoan islands, just below the equator and half way between Honolulu and Auckland that the Polynesian people, “the most remarkable seafaring people in history”1, sailed forth to become the Māori of New Zealand, and the first human visitors to Easter Island. It was from Samoa that they migrated to Tahiti and from there on to Hawai’i. Growing up in those islands I came to view the Samoans as the hardcore Polynesians, they were the big guys in the toughest gangs in the schoolyard. They played the hardest: confusing sportsmanship with pain on the playing fields and in the lineup out on the breakers. I also remained enchanted by the great Pacific Ocean long into adulthood and could never shake my childhood impression that the Samoans were the only people to master that vast body of water, the single largest piece of the planet. There came a time when felt compelled to go to Samoa, slide into the heart of Polynesia and climb to the peak of Mt.’Alava where I could see the Pacific’s horizon 360degrees around me; to stand where the high chiefs of ancient Samoa stood and, for some reason, said to each other “lets sail out that way.” I wanted to drink their coolaid; feel whatever mystical pull that made them do it. So I went and what I found out changed my entire perspective, not only about how the Polynesian did it but of the white man’s way of recording history.

Samoa is the heartland of Polynesia. It was from the Samoan islands, just below the equator and half way between Honolulu and Auckland that the Polynesian people, “the most remarkable seafaring people in history”1, sailed forth to become the Māori of New Zealand, and the first human visitors to Easter Island. It was from Samoa that they migrated to Tahiti and from there on to Hawai’i. Growing up in those islands I came to view the Samoans as the hardcore Polynesians, they were the big guys in the toughest gangs in the schoolyard. They played the hardest: confusing sportsmanship with pain on the playing fields and in the lineup out on the breakers. I also remained enchanted by the great Pacific Ocean long into adulthood and could never shake my childhood impression that the Samoans were the only people to master that vast body of water, the single largest piece of the planet. There came a time when felt compelled to go to Samoa, slide into the heart of Polynesia and climb to the peak of Mt.’Alava where I could see the Pacific’s horizon 360degrees around me; to stand where the high chiefs of ancient Samoa stood and, for some reason, said to each other “lets sail out that way.” I wanted to drink their coolaid; feel whatever mystical pull that made them do it. So I went and what I found out changed my entire perspective, not only about how the Polynesian did it but of the white man’s way of recording history.

* * *

Like the big bang that created all of the cosmos no one really knows where the settlement of the Pacific really began but we are clear on where it ended. Ten thousand years ago the Lapita people left New Guinea2 or the Neolithic Hemudu shoved off of the China3 coast sailing forth against the prevailing winds and currents in open canoes, crude sails of woven pandanus and planking tied together with coconut rope4; no more than Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn had when they drifted down the Mississippi in the 1876. By 1,000 CE these seafarers had settled just about every inhabitable land mass in the 30million square miles of the Pacific Ocean5 that is now called the Polynesian Triangle. In the last phase of this Great Polynesian Migration, when they sailed from Samoa in fleets of up to 100 boats, loaded with chicken, pigs, extended families6 from where they would establish themselves on every inhabitable island in the central Pacific. The wayfinders who piloted these fleets obviously knew what they were doing. They could only provision their boats to survive 20 days at sea7so they would have to island hop their way across the vast ocean. Much of Polynesian folklore is built around the mystical powers of the wayfinders, as Miss Wahineaukai had taught us in fifth grade, but in fact the Great Polynesian Migration owes its safety and success to learn skills and solid science. The critical measurement of successful navigation, points out Jack Lagan, a contemporary navigator instructor, lies not in the discovery of new islands in the middle of the ocean, “rather in the ability to find them agian.”8 Captain James Cook demonstrated that to the literate world in the late 1770’s. The Polynesian had mastered that skill some 800 years before that.

When Cook first “discovered” Tahiti in 1769 he took onboard a “priest” named from Tupaia who was from the distant island of Ratata9—confusing, once again, the spiritual title of high priest with the role of wayfinder, which is what he was. Without referring to instruments or charts, Tupaia guided Cook 300nm south to the tiny Polynesian island of Rurta. As sort of a parlor game some of Cooks officers sketched out a chart as Tupaia described the South Pacific from memory, creating what they called “Tupaia’s cranial map.”10 Tupaia didn’t just know the he names of 70 separate island groups through the Polynesian Triangle “he knew where they were and how to get to them.” You can see Tupaia’s chart today in the Manuscript Collection of the British Library in London 11 and you can see just how accurately it lays out the tiny islands throughout the Pacific. If you were a Polynesian you wouldn’t need a map top find your way around the Pacific—you’d know how to get where you were going without it.

So how did they do it? How did they cross 3,000nm of ocean in open canoes reliably returning to their home island then sailing off again like trains out of Grand Central Station. They had no charts, no compass, no chronometer, no sextant, no GPS, and no written tradition to pass information down to succeeding generations. The “fundamental elements of the Polynesian world: water, waves, clouds, stars, sun, moon, birds, fish and water itself. Bring to that the raw power of empirical observation, of universal human inquiry. The skills of the [Polynesian wayfinder] are not unlike those of a scientist.”12 Star paths are quite reliable but not always visible. The wayfinders did not perceive themselves as moving towards a point on a chart. Rather they saw their boat as a fixed point with “distant islands moving towards the navigator.”13 The most reliable constant in the open sea are the trade winds and the swells. If you can learn to distinguish the feel of the prevailing breezes from the constant trade winds and if you can teach yourself to senses the difference between the surface waves and the pull of the deeper current you could find your way reliably to places that were thousands of miles away from each other. Polynesian wayfinders were known to lay in the deck of their twin-hulled wakas for long periods[citation needed] so they could cognate the rhythmic expanding and contracting of the water pressures. A sailor at the helm could then, and can now, reliably keep a boat on course for days by keeping the primary swell pushing consistently against the boats port quarter* Long before an island is visible the keen wayfinder can feel the reflected swell pushing off of the land mass and, similarly there is no metaphysical spirit involved when they sense a refracted swell, the back wash of a land mass they are sailing past.

Then there are the clouds and/or fog that form when the moist air over the sea rises when it blows into the solid mass of an island; and the birds. All seafaring people know that large Frigate Birds feed far out to sea, up to 70mn from land and smaller birds like the Brown Noddy can’t make it more than 20mn offshore.14 The smaller the bird the shorter the shorter the feeding range therefore the closer to land you must be. Crossing the Pacific in an open canoe is a daunting challenge, but, like a mountain climber that can see the peak overhead, the Polynesians did not have a problem knowing where they were or where they were going. That was a matter of staying tuned into the natural elements of their world.

* * *

In yacht clubs and bars overlooking the Pacific today the great debate among sailors, the folks who cross the waters in under sail, is between the old salts who rely on traditional navigation (using sextants, compass, and chronometers) who look despairingly on the young skippers who can’t find their next port without a GPS device. “That’s not sailing,” I hear the old salts complain. “What would they do if their electricity goes out?”

Well, the GPS skippers could do the same thing that the old salts could do when they drop their sextants on the deck, is my answer. They could stick their head out of the companionway and take a look at the world that they are sailing through.

As is should be, the fear of being lost as sea has long been the great deterrent to ocean cruising, and the advent of GPS navigation has changed that significantly. There are twice as many blue water sailing passages being made today than there were in 2006.“In all the planet’s seas, at any given time, there are about 10,000 cruising boats taking long-term transoceanic voyages.”15 Navigation skills once acquired by the manipulation of esoteric contraptions (like the sextant) and classroom certification are easily replaced with idiot-proof technology: “a GPS trumps a sextant . . . and an iPad makes a fantastic chart plotter.”16 Personally I find this debate rather moot, at best an amusing drinking conversation. Both the old and new navigation technologies serve to distance us from the natural world that we seek. “The history of navigation is the history pursuit of accuracy.”17 Jack Logan reminds us and from that perspective it is a matter of putting dots on the map with greater precision. But there is much more to it. Dr. Tianlog Jiao, anthropologist with Honolulu’s Bishop Museum, takes a much grander view of ocean navigation: “The whole story is about migration, but it’s also about diversity, struggle and resilience. It’s about understanding one’s ancestral roots . . . and at the same time realizing that we are all connected.” 18 Wow, and I thought that I was just trying not to get lost out there.

One of the subtle pleasures that I always get after period at sea is the rhythm of the ocean that lingers in the fluid of my body in those first uneasy steps on terra firma that remind me that my body had actually acclimated to a different surface of our planet. I can literally feel that in my bones. And I don’t need a map or a guidebook to tell me that. The more measurements that we use to master the earth the more we lose our feel for the world that we live in.

140613 -1,844words

Tianlong Jiao, Anthropologist at Honolulu’s Bishop Museum (Department Chair from 2016 to 2013) as quoted in Hana Hau! V16 #5 Oct/Nov 2013.

Wade Davis, “The Wayfinders”, National Geographic Adventure magazine, Dec 07 – Jan 08 issue.

IBID, Jiao.

IBID, Davis

Jack Lagan, The Barefoot Navigator, Sheridan House, NY. 2006, 2010

Jan Knappert, Pacific Mythology, Diamond Books, London, 1995 edition.

Sir Joseph Banks, The Endeavour Journal, 25 August 1778-July 1771. Entry for 21 July 1769.[/fusion_menu_anchor]

IBID, Lagan.

Anne DiPiazza and Erik Pearthree, “History of an Idea About Tupaia’s Chart’”, The Captain Cook Society, Wickford, Essex, UK as published in captaincooksociety.com, © 1996-2014.

IBID, Lagan. Pg 9.

IBID, DiPiazza & Pearthree.

IBID, Davis.

IBID, DiPiazza & Pearthree.

( * ) Or any other portion of the hull.

IBID, Lagan who has an entire chart of birds and the distances they can travel from land.

Sara Rose, “Escaping the Recession by Boat,” Outside Magazine, August 2013.

IBID, Sara Rose

IBID, Jack Logan

IBID, Dr. Tianlong Jiao

Fa’a Samoa is a colloquial term that refers to the Samoan way of doing things.

The Only Cuban Cigar I Truly Enjoyed

The way that I remember it we are in The Club Cohiba drinking Mojitos—or was in Martinis? Dark and exotic, The Club Cohiba lies beneath the ground floor of the Havana Hotel in San Antonio, which, after the coming and going of several elegant cocktail glasses, takes on a shivery conspiratorial air. Across the room old men in pencil-thin moustaches and hard glances thrash out yet another plot to assassinate Fidel Castro, or maybe they are playing canasta. Andres (“you may call me Andy”) Lagueruela and I are engaged in kind of an oral foreplay with these cigars Andy had brought—not Cuban cigars, they would have none of that in this place—rather cigars brought in through friendly Nicaragua but grown from Cuban seeds, like the clientele here. Equally portly and affable Andy is truly enjoying his smoke while I am merely pretending. I had succumbed to the Cigar Aficionado dernier cri that had afflicted my demographic at the time but, really, cigars are disgusting; although a useful prop on this stage.

The hotel elevator is the entry to The Club Cohiba and opens like a stage door cueing a couple ready to Tango: he, a baggy suit under a cocked Fedora, and she with her cherry-red lipstick matched to her cherry-red and skin-tight dress that had me, and every other male in the place, follow the long line of her leg down to her cherry-red stiletto heels. My eyes follow them, more specifically her, as they cross the floor to the bar when Andy jars me back to the present.

The hotel elevator is the entry to The Club Cohiba and opens like a stage door cueing a couple ready to Tango: he, a baggy suit under a cocked Fedora, and she with her cherry-red lipstick matched to her cherry-red and skin-tight dress that had me, and every other male in the place, follow the long line of her leg down to her cherry-red stiletto heels. My eyes follow them, more specifically her, as they cross the floor to the bar when Andy jars me back to the present.

“Lagueruela! If you were at all Latin you would know the name Lagueruela.”

“Well, no . . .”

He draws from his cheroot and leans into my face, not threatening at all, more of a mannerism of Latin intimacy. I find it peculiar how he can speak so empathetically with a lung full of cigar smoke, not a wisp of it escaping from his mouth as he says: “We were Cuba before 1959.

“Lagueruelas were both sides of the Cuban War of Independence. Lagueruelas were the sugar plantations and the rum distillers. We owned all the concrete made in Cuba until the island fell.”

Hmm, one of Colonel’s Batista’s cronies, I am thinking. “So you didn’t leave Cuba on the best of terms.”

He leans back and lets the blue smoke creep from his mouth. “My heart never left Cuba.” The look on his face is more melancholy than bitter. “The Crocodile,” he laughs. “You know that the island takes the shape of a crocodile.”

I nod even though that was news to me. I want to take this in another direction. “Ever been back?” I draw in on my cigar and cough a bit then take a slow sip of my . . .whatever it is . . . to cover it up.

“Not officially,” he says with a mischievous wink.

Sensing that we have reached a boundary in our relationship and bolstered by the rum—or was it gin?—I press on endeavoring to impress him with my familiarity of the issue. “So you were Omega?” I drop the code name.

He offers up a gamey smile, as if I had taken a point in a game of What’s-My-Line and nothing more serious than that.

“Bay of Pigs?” I ask.

“Of course.” Nodding.

So I haven’t even scratched the surface of this conversation and my cigar is becoming more enjoyable. I had met Andy through work. I had figured out that it was his quite public relations firm that was getting all the cost-plus federal assignments like the Base Realignment and Closure projects and it was his agency that came up with “Jack Hammer” for the national slow-down-for-highway-workers campaign. All of that required high level, insider, federal favor pay-back and I was digging for some subcontractor work out of him when he answers my unasked question:

“Yes, they know me at CIA. And Lagueruela is even better known in Cuba where there is a price on my head.”

So what do I say now, me the inebriated interviewer? The door is open and the next question is critical. I am searching through the fog of my intoxication but come up with nothing but another drink. Who ordered those?

Smoke rings glide from his lips as Andy laughs and continues on his own. “At one time, my friend, I get a call. This was just after the Missile Crisis. Do you know the Missile Crisis?”

“Of course.”

Apparently, he tells me, some CIA operatives had acquired a Soviet Officer’s parade uniform that would fit Andy—a rare find because Andy was beyond a 3X. The operatives were quite excited about his, as if this was “it”; the one thing that was certain to topple Fidel. Andy, of course was game. He was hustled out to New Mexico where, at a top secret federal facility, where he was trained in high-altitude parachuting. Now, just looking at Andy as he winds out this tale of espionage and intrigue, I can tell that he has always been more of a gourmet that an athletic-type and he must have gone about this specialized combat training with an odd combination of patriotism and dégagé. He was certain to die. Andy puffs himself up as he tells me about the jump: he was actually pushed out of a high-altitude AWAC. “I would have jumped on my own but I thought that it was just a moment too soon.” He wore an oxygen mask for the freefall part of the drop and a large wrist watch that told him when he reached the altitude where he was supposed to could pull his ripcord. It was his only parachute jump he ever attempted and the mission was a complete success: he landed close to where he was supposed to, on a plantation that used to be owned by a former brother-in-law. Contacts from Omega met him in the field; he was scurried off to a series of to a safe house, hiding in the jungle in a Soviet officers dress uniform, and eventually smuggled out of the country in a fishing boat, still dressed for a parade on Red Square. The mission was a complete success.

“What did you do? What was the mission?” I ask.

“Just that.” His cigar is well poised and he releases the smoke as if it was a sentence in our give-and-take. “I crept in. I crept out.” And when the blue smoke of the Nicaraguan tobacco from Cuban seed cleared a look of great disappointment filled his eyes and he spoke with a sarcastic inflection, “Another blow to the regime.”

“What’s the point?” My words managed to fall from my cotton-dry mouth.

Andy leans into me once again. If not for the tiny table between us he may have fallen into my lap. “This is how you American spend your money and,” he pushes a stubby finger into my face, “and this is the fate of my country.”

Andy manages to find his way to his feet: cigar still in hand as he lumbers off to find the bathroom. I snuff out my cigar in the ash tray, take an olive from the Martini glass and plop it in my mouth as my eyes slowly cast about the room. The Tango dancer in cherry-red has attracted a few more men to the bar. The junta of canasta players unabashedly lay their hard glances on me, perhaps as a warning, wondering if their chubby spy chief was reveling too much information and I realize with a sudden and hardy laugh that I am a background character in a black-and-white, B-movie.* * *

Andy returns refreshed and pulling two new cigars from the inside pocket of his wrinkled linen suit coat while a white jacketed waiter following him with two exquisite cocktail glasses on a tray. I had had enough but I would certainly have more. Andy fell into his seat, passed me one of his un-banded cigars and went to work on his with a silver sniper; carefully clipping a tiny piece off of the cap-end before sticking it in his mouth like a pop-cycle to moisten the head wrapper. I attempted to mimic his savoir faire and managed to get mine lit without causing a fire.

The action of smoking the cigar became an integral part of Andy’s dialog; he leaned back in his chair and drew in a long toke. “I have permission to return.” He paused, met my eyes and exhaled a veil of thin blue smoke. “But I am not certain that it will honored.”

“Cuba, you mean?” I exhaled in kind.

“They could easily pick me up at the airport and you, my friend, will never know how the story ends.”

I attempted to use my cigar as dialog, inhaling, leaning back and giving his a look that was mean to say “go on.”

“My mother’s older sister and her family are still in Havana, living in part of a house we once owned. The house has become run down. She shares it with others. They have electricity frequently enough but the old elevator hasn’t worked for, I don’t know how long. To get water to her bathroom on the third floor they have a garden hose dropped from her balcony to a spigot on the street. She is getting old and she has the last I have heard, the matching pistol.”

“Pistol?”

“One of two….”

Andy paused as if to consider . . . what? Martini or cigar? Whether or not he should tell me? Tell me what? Whatever it was I was eager for the next act in this B-movie so I chose the tact that had served me so well earlier in the evening: I remained silent. Aver a sip from his martini and a pull on his cigar Andy gave me a wry smile and I know that I would have it.

Andy told me that his great grandfather was the last Governor General of Cuba to be appointed by the Spanish Crown. He brought with him a deep swath of Spanish history and two hand-tooled dueling pistols that had been in his family since the Castilian period. They were the old mussel-loading kind that fired by a flintlock apparatus, the kind gentlemen in white wigs and white hosiery used to settle disputes before the days of Judge Judy.

Although a Court appointed autocrat Grandpa Lagueruela, Andy tells me, had had some degree of political savvy. This was the late ninetieth century when Spain was going through the long agonizing process of losing its Caribbean colonies one-by-one and it was Cuba’s turn to fall. In the ancient way of collapsing monarchs—a technique that had work so for Castilians in the sixteenth century, when those elegant pistols were made—Governor General Lagueruela married into an old Cuban Creole family expecting, Andy assumes, that such a union would mends some fences with the locals. That didn’t work out so well. Señora Laugueruela’s deeper sympathies lay with the more liberal causes and their oldest son was sent to Princeton University in the United States where he became sympathetic with the Mambises and, to scoot right to the end of a more complex journey, Andy’s grandpa ended up serving as an aide-de-camp to Teddy Roosevelt as he charged his Rough Riders up San Juan Hill to topple the Spanish.

“I have seen the letter that my grandfather received from his father, the Governor General. It is written in his very elegant hand on an oversized piece of parchment, more like a manifesto than a letter to his own son. My great grandfather had an exceptionally dramatic command of a beautiful language. The words themselves brought tears to my eyes.”

Andy is out of cigar and martini at this point and I with my two-toke cheroot smoldering in the ashtray and my cocktail glass either half-full or half-empty continue to hold up the silent side of our conversation with an encouraging nod.

“I paraphrase here, of course. I could never match the phrasing of the caudillo.” He nodded: we were locked eye-to-eye. “The letter told of his aspirations for his son and he spared no sentiment telling of his love.”

The letter accompanied one of the two dueling pistols complete with powder and shot. “Carry this with you at all times in the upcoming conflict,” the Governor General instructed his son, “as I will carry the other. When we cross paths, como vamos a, you must put a bullet straight through my heart—me mata muertos,” was the way that Andy recalled the wording, “and you must do this before I take your life, for I certainly will.”

I lean it to catch each of the word that fell from Andy’s lips. His voice begins to slur and his words are alternating too frequently between Spanish and English. The gin, it seemed, was getting the best of him as I was rapidly sobering in the resplendence of his compelling novella. Andy said something of the Governor General bearing the double burden of killing both a traitor to Spain and the bearing sin of killing his own son; therefore he expressed, according to Andy, a hoped that the son would dispatch him first.

Andy seems content to end his story with the end of the letter, or perhaps he is too wasted to continue so I speak up. “So, what happened? Did they cross paths?”

“Ah yes, the moment of angst came at the surrender, when it was time for the Governor General to surrender his sword to the armies of Cuban independence. My grandfather, still the aide-de-camp to the Americans, was in attendance.”

“With is dueling pistol?”

“Quite possibly. I don’t really know.” Andy pauses and takes a breath. I can see that this story has exhausted him. “The stories that are passed down on my side of the family tell of how the Governor General, having lost Cuba for his country and having a sworn pledge to fulfill, loaded his pistol with shot and power and placed in in the leather holder that he was going to wear to the surrender. Some of his staff testifies to this.”

Another long pause and Andy searched his memory.

“And? Did they meet?”

“No,” he said abruptly. “The old man suffered a fatal heart attack in his carriage on the way to the surrender ceremony.”

A dense uncertainty freezes for a long moment before Andy unleashed a loud and uncontrolled barrel laugh. I break into laughter with him, though not really knowing what was funny. Our laughter is loud and contagious enough for the conspirators at the canasta table to join in our laughter which captured the attention of the Tango group at the bar to turn and join in. For what? Nobody, not even me, knew where the humor lay except that we were drinking a laughing and some of that story may have been true.

* * *

Apparently the letter of the Governor General and one of the dueling pistols are now with the Lagueruelas in Miami. This would be the set that Andy was familiar with. The other pistol remains with the Lagueruelas who stayed in Cuba. Andy’s true mission is to reconnect with the family that he left behind in Cuba and the tale of the two pistols give him a colorful cause célèbre to justify his journey home.

I snagged the bill when it came. Andy held his hand out insisting that he pay.

“No, please. Andy. This is on me.”

He tried to pull the chit from my hand, we were both drunk and stumbly so the billet fell on to the table and stuck to a wet spot. Andy’s fat hand came down on top of mine as I tried to pick it up and we argued playful love which one of us would pay. I can’t remember which of us won but I do remember the two of us stumbling arm-in-arm down Navarro Street trying to remember where we had parked our cars.

140817 -2,685words

Andy Lagueruela did return to Havana in January 1998 and he was not arrested at the airport. Pope John Paul II was scheduled to make his historic visit to Cuba at the end of January and all foreign aliens were summarily required to vacate the island. So Andy was obliged to leave Cuba before he was able to catch up with the aunt who was alleged to have the patching dueling pistol.

Although the Spanish changed commanders on a rapid basis in their final years of mis-ruling Cuba, my cursory research could not find the name Lagueruelas in any of their rosters. The infamous Valeriano Weyler was the last to have the title Governor General a position he held from 1896 to 1897. He was replaced by Ramón Blanco who had the title Captain General of Cuba from 1897 to 1898. The Spanish got to surrender several times in the War of Cuban Independence. On July 17th 1998 it was a field general, José Toral, divisional commander of the Spanish IV Corp who surrendered Santiago to Joseph Wheeler and it was a dude named Adolfo Jiménez Castellanos with the title of Captain General in Havana who had the pleasure of formally surrendering all of Cuba to the Americans on January 1, 1899. No one had a heart attack on the way to the surrender ceremony.

Five Days With The Huaorani

Huaorani consider themselves to be the bravest people in the Amazon. Through uncountable millennia they have defended their piece of the Oriente rainforest by killing everyone and anyone who they come across who was not Huaorani. Their spears were left in the bodies of the trespassers to ensure that their message was clear. The great expanse of the Aztec civilization avoided them and the Spanish empire dared not encroach on their part of the Amazon. Not even The Liberator, Simon Bolivar, would take his indefatigable troops into the Huaorani’s small piece of Ecuador. Today they stand up against a foe that they know will destroy the rainforest and put an end to their way of life: Big Oil. At the time that I was born, no one in the world who knew how to read or write was even aware that the Huaorani existed. By the time that I die they will be extinct. That is why we had to go.

What struck me immediately was that the jungle is not the scary place I had imagined. It is the Garden of Eden—the most bio-diverse place on the planet. There was a plethora of insects but they were not swarming in your face all the time. You had to be ever vigilant for snakes, scorpions, and other dangers beneath your feet. If you stumbled on a trail you did not reach out for a branch to steady yourself; it may have toxic stickers or the dreaded Conga ants that could paralyze your entire arm with one painful bite. You just let yourself fall to the ground; or better yet, you learned to walk more thoughtfully down the jungle path. It was wet and muddy.

What struck me immediately was that the jungle is not the scary place I had imagined. It is the Garden of Eden—the most bio-diverse place on the planet. There was a plethora of insects but they were not swarming in your face all the time. You had to be ever vigilant for snakes, scorpions, and other dangers beneath your feet. If you stumbled on a trail you did not reach out for a branch to steady yourself; it may have toxic stickers or the dreaded Conga ants that could paralyze your entire arm with one painful bite. You just let yourself fall to the ground; or better yet, you learned to walk more thoughtfully down the jungle path. It was wet and muddy.

The humidity could reach 100% but we were shaded and never far from the cool, flowing waters of the Shiripuno River. The jungle, I learned, could create its own rain shower when the evaporation of moisture from the understory was trapped under the broadleaves of the higher canopy.

Fa’a Samoa

It is awfully difficult for a barefoot school boy to pay attention to his lessons with the Pacific Ocean pounding on the beach just beyond the playground of Mokapu Elementary School. Even with less than half of my attention in the classroom I do remember Miss Wahineaukai teaching us, in her Pigeon-English, about the first Polynesians to settled in the Hawai’ian islands such a long time ago. With no compass or maps, with no written tradition in their culture, they sailed into the tiny island chain—the most remote body of land in the planet—after months in open canoes. Luck, I imagined: like seeds blown from a dandelion, a few found fertile ground but most of them perished at sea. The words of that Miss Wahineaukai that stayed with me through my entire life were “the wayfinders who guided these boats were high priest who had been given the vision and talked to the Gods of the sea. All of the strong kanes who manned the paddles placed their absolute faith and obedience in the wayfinder.”

Yeah! I got that. The only way that I would get in an open canoe and paddle out into the endless ocean for months on end, where I was probably going to die, would be if I had a delusional faith in the man at the helm. These Polynesian dudes were crazy—or driven by something that I had yet to understand, something in the seductive call of the Pacific Ocean.

Samoa is the heartland of Polynesia. It was from the Samoan islands, just below the equator and half way between Honolulu and Auckland that the Polynesian people, “the most remarkable seafaring people in history”1, sailed forth to become the Māori of New Zealand, and the first human visitors to Easter Island. It was from Samoa that they migrated to Tahiti and from there on to Hawai’i. Growing up in those islands I came to view the Samoans as the hardcore Polynesians, they were the big guys in the toughest gangs in the schoolyard. They played the hardest: confusing sportsmanship with pain on the playing fields and in the lineup out on the breakers. I also remained enchanted by the great Pacific Ocean long into adulthood and could never shake my childhood impression that the Samoans were the only people to master that vast body of water, the single largest piece of the planet. There came a time when felt compelled to go to Samoa, slide into the heart of Polynesia and climb to the peak of Mt.’Alava where I could see the Pacific’s horizon 360degrees around me; to stand where the high chiefs of ancient Samoa stood and, for some reason, said to each other “lets sail out that way.” I wanted to drink their coolaid; feel whatever mystical pull that made them do it. So I went and what I found out changed my entire perspective, not only about how the Polynesian did it but of the white man’s way of recording history.

Samoa is the heartland of Polynesia. It was from the Samoan islands, just below the equator and half way between Honolulu and Auckland that the Polynesian people, “the most remarkable seafaring people in history”1, sailed forth to become the Māori of New Zealand, and the first human visitors to Easter Island. It was from Samoa that they migrated to Tahiti and from there on to Hawai’i. Growing up in those islands I came to view the Samoans as the hardcore Polynesians, they were the big guys in the toughest gangs in the schoolyard. They played the hardest: confusing sportsmanship with pain on the playing fields and in the lineup out on the breakers. I also remained enchanted by the great Pacific Ocean long into adulthood and could never shake my childhood impression that the Samoans were the only people to master that vast body of water, the single largest piece of the planet. There came a time when felt compelled to go to Samoa, slide into the heart of Polynesia and climb to the peak of Mt.’Alava where I could see the Pacific’s horizon 360degrees around me; to stand where the high chiefs of ancient Samoa stood and, for some reason, said to each other “lets sail out that way.” I wanted to drink their coolaid; feel whatever mystical pull that made them do it. So I went and what I found out changed my entire perspective, not only about how the Polynesian did it but of the white man’s way of recording history.

* * *

Like the big bang that created all of the cosmos no one really knows where the settlement of the Pacific really began but we are clear on where it ended. Ten thousand years ago the Lapita people left New Guinea2 or the Neolithic Hemudu shoved off of the China3 coast sailing forth against the prevailing winds and currents in open canoes, crude sails of woven pandanus and planking tied together with coconut rope4; no more than Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn had when they drifted down the Mississippi in the 1876. By 1,000 CE these seafarers had settled just about every inhabitable land mass in the 30million square miles of the Pacific Ocean5 that is now called the Polynesian Triangle. In the last phase of this Great Polynesian Migration, when they sailed from Samoa in fleets of up to 100 boats, loaded with chicken, pigs, extended families6 from where they would establish themselves on every inhabitable island in the central Pacific. The wayfinders who piloted these fleets obviously knew what they were doing. They could only provision their boats to survive 20 days at sea7so they would have to island hop their way across the vast ocean. Much of Polynesian folklore is built around the mystical powers of the wayfinders, as Miss Wahineaukai had taught us in fifth grade, but in fact the Great Polynesian Migration owes its safety and success to learn skills and solid science. The critical measurement of successful navigation, points out Jack Lagan, a contemporary navigator instructor, lies not in the discovery of new islands in the middle of the ocean, “rather in the ability to find them agian.”8 Captain James Cook demonstrated that to the literate world in the late 1770’s. The Polynesian had mastered that skill some 800 years before that.

When Cook first “discovered” Tahiti in 1769 he took onboard a “priest” named from Tupaia who was from the distant island of Ratata9—confusing, once again, the spiritual title of high priest with the role of wayfinder, which is what he was. Without referring to instruments or charts, Tupaia guided Cook 300nm south to the tiny Polynesian island of Rurta. As sort of a parlor game some of Cooks officers sketched out a chart as Tupaia described the South Pacific from memory, creating what they called “Tupaia’s cranial map.”10 Tupaia didn’t just know the he names of 70 separate island groups through the Polynesian Triangle “he knew where they were and how to get to them.” You can see Tupaia’s chart today in the Manuscript Collection of the British Library in London 11 and you can see just how accurately it lays out the tiny islands throughout the Pacific. If you were a Polynesian you wouldn’t need a map top find your way around the Pacific—you’d know how to get where you were going without it.

So how did they do it? How did they cross 3,000nm of ocean in open canoes reliably returning to their home island then sailing off again like trains out of Grand Central Station. They had no charts, no compass, no chronometer, no sextant, no GPS, and no written tradition to pass information down to succeeding generations. The “fundamental elements of the Polynesian world: water, waves, clouds, stars, sun, moon, birds, fish and water itself. Bring to that the raw power of empirical observation, of universal human inquiry. The skills of the [Polynesian wayfinder] are not unlike those of a scientist.”12 Star paths are quite reliable but not always visible. The wayfinders did not perceive themselves as moving towards a point on a chart. Rather they saw their boat as a fixed point with “distant islands moving towards the navigator.”13 The most reliable constant in the open sea are the trade winds and the swells. If you can learn to distinguish the feel of the prevailing breezes from the constant trade winds and if you can teach yourself to senses the difference between the surface waves and the pull of the deeper current you could find your way reliably to places that were thousands of miles away from each other. Polynesian wayfinders were known to lay in the deck of their twin-hulled wakas for long periods[citation needed] so they could cognate the rhythmic expanding and contracting of the water pressures. A sailor at the helm could then, and can now, reliably keep a boat on course for days by keeping the primary swell pushing consistently against the boats port quarter* Long before an island is visible the keen wayfinder can feel the reflected swell pushing off of the land mass and, similarly there is no metaphysical spirit involved when they sense a refracted swell, the back wash of a land mass they are sailing past.

Then there are the clouds and/or fog that form when the moist air over the sea rises when it blows into the solid mass of an island; and the birds. All seafaring people know that large Frigate Birds feed far out to sea, up to 70mn from land and smaller birds like the Brown Noddy can’t make it more than 20mn offshore.14 The smaller the bird the shorter the shorter the feeding range therefore the closer to land you must be. Crossing the Pacific in an open canoe is a daunting challenge, but, like a mountain climber that can see the peak overhead, the Polynesians did not have a problem knowing where they were or where they were going. That was a matter of staying tuned into the natural elements of their world.

* * *

In yacht clubs and bars overlooking the Pacific today the great debate among sailors, the folks who cross the waters in under sail, is between the old salts who rely on traditional navigation (using sextants, compass, and chronometers) who look despairingly on the young skippers who can’t find their next port without a GPS device. “That’s not sailing,” I hear the old salts complain. “What would they do if their electricity goes out?”

Well, the GPS skippers could do the same thing that the old salts could do when they drop their sextants on the deck, is my answer. They could stick their head out of the companionway and take a look at the world that they are sailing through.

As is should be, the fear of being lost as sea has long been the great deterrent to ocean cruising, and the advent of GPS navigation has changed that significantly. There are twice as many blue water sailing passages being made today than there were in 2006.“In all the planet’s seas, at any given time, there are about 10,000 cruising boats taking long-term transoceanic voyages.”15 Navigation skills once acquired by the manipulation of esoteric contraptions (like the sextant) and classroom certification are easily replaced with idiot-proof technology: “a GPS trumps a sextant . . . and an iPad makes a fantastic chart plotter.”16 Personally I find this debate rather moot, at best an amusing drinking conversation. Both the old and new navigation technologies serve to distance us from the natural world that we seek. “The history of navigation is the history pursuit of accuracy.”17 Jack Logan reminds us and from that perspective it is a matter of putting dots on the map with greater precision. But there is much more to it. Dr. Tianlog Jiao, anthropologist with Honolulu’s Bishop Museum, takes a much grander view of ocean navigation: “The whole story is about migration, but it’s also about diversity, struggle and resilience. It’s about understanding one’s ancestral roots . . . and at the same time realizing that we are all connected.” 18 Wow, and I thought that I was just trying not to get lost out there.

One of the subtle pleasures that I always get after period at sea is the rhythm of the ocean that lingers in the fluid of my body in those first uneasy steps on terra firma that remind me that my body had actually acclimated to a different surface of our planet. I can literally feel that in my bones. And I don’t need a map or a guidebook to tell me that. The more measurements that we use to master the earth the more we lose our feel for the world that we live in.

140613 -1,844words

Tianlong Jiao, Anthropologist at Honolulu’s Bishop Museum (Department Chair from 2016 to 2013) as quoted in Hana Hau! V16 #5 Oct/Nov 2013.

Wade Davis, “The Wayfinders”, National Geographic Adventure magazine, Dec 07 – Jan 08 issue.

IBID, Jiao.

IBID, Davis

Jack Lagan, The Barefoot Navigator, Sheridan House, NY. 2006, 2010

Jan Knappert, Pacific Mythology, Diamond Books, London, 1995 edition.

Sir Joseph Banks, The Endeavour Journal, 25 August 1778-July 1771. Entry for 21 July 1769.[/fusion_menu_anchor]

IBID, Lagan.

Anne DiPiazza and Erik Pearthree, “History of an Idea About Tupaia’s Chart’”, The Captain Cook Society, Wickford, Essex, UK as published in captaincooksociety.com, © 1996-2014.

IBID, Lagan. Pg 9.

IBID, DiPiazza & Pearthree.

IBID, Davis.

IBID, DiPiazza & Pearthree.

( * ) Or any other portion of the hull.

IBID, Lagan who has an entire chart of birds and the distances they can travel from land.

Sara Rose, “Escaping the Recession by Boat,” Outside Magazine, August 2013.

IBID, Sara Rose

IBID, Jack Logan

IBID, Dr. Tianlong Jiao

Fa’a Samoa is a colloquial term that refers to the Samoan way of doing things.

The Only Cuban Cigar I Truly Enjoyed

The way that I remember it we are in The Club Cohiba drinking Mojitos—or was in Martinis? Dark and exotic, The Club Cohiba lies beneath the ground floor of the Havana Hotel in San Antonio, which, after the coming and going of several elegant cocktail glasses, takes on a shivery conspiratorial air. Across the room old men in pencil-thin moustaches and hard glances thrash out yet another plot to assassinate Fidel Castro, or maybe they are playing canasta. Andres (“you may call me Andy”) Lagueruela and I are engaged in kind of an oral foreplay with these cigars Andy had brought—not Cuban cigars, they would have none of that in this place—rather cigars brought in through friendly Nicaragua but grown from Cuban seeds, like the clientele here. Equally portly and affable Andy is truly enjoying his smoke while I am merely pretending. I had succumbed to the Cigar Aficionado dernier cri that had afflicted my demographic at the time but, really, cigars are disgusting; although a useful prop on this stage.

The hotel elevator is the entry to The Club Cohiba and opens like a stage door cueing a couple ready to Tango: he, a baggy suit under a cocked Fedora, and she with her cherry-red lipstick matched to her cherry-red and skin-tight dress that had me, and every other male in the place, follow the long line of her leg down to her cherry-red stiletto heels. My eyes follow them, more specifically her, as they cross the floor to the bar when Andy jars me back to the present.

The hotel elevator is the entry to The Club Cohiba and opens like a stage door cueing a couple ready to Tango: he, a baggy suit under a cocked Fedora, and she with her cherry-red lipstick matched to her cherry-red and skin-tight dress that had me, and every other male in the place, follow the long line of her leg down to her cherry-red stiletto heels. My eyes follow them, more specifically her, as they cross the floor to the bar when Andy jars me back to the present.

“Lagueruela! If you were at all Latin you would know the name Lagueruela.”

“Well, no . . .”

He draws from his cheroot and leans into my face, not threatening at all, more of a mannerism of Latin intimacy. I find it peculiar how he can speak so empathetically with a lung full of cigar smoke, not a wisp of it escaping from his mouth as he says: “We were Cuba before 1959.

“Lagueruelas were both sides of the Cuban War of Independence. Lagueruelas were the sugar plantations and the rum distillers. We owned all the concrete made in Cuba until the island fell.”

Hmm, one of Colonel’s Batista’s cronies, I am thinking. “So you didn’t leave Cuba on the best of terms.”

He leans back and lets the blue smoke creep from his mouth. “My heart never left Cuba.” The look on his face is more melancholy than bitter. “The Crocodile,” he laughs. “You know that the island takes the shape of a crocodile.”

I nod even though that was news to me. I want to take this in another direction. “Ever been back?” I draw in on my cigar and cough a bit then take a slow sip of my . . .whatever it is . . . to cover it up.

“Not officially,” he says with a mischievous wink.

Sensing that we have reached a boundary in our relationship and bolstered by the rum—or was it gin?—I press on endeavoring to impress him with my familiarity of the issue. “So you were Omega?” I drop the code name.

He offers up a gamey smile, as if I had taken a point in a game of What’s-My-Line and nothing more serious than that.

“Bay of Pigs?” I ask.

“Of course.” Nodding.

So I haven’t even scratched the surface of this conversation and my cigar is becoming more enjoyable. I had met Andy through work. I had figured out that it was his quite public relations firm that was getting all the cost-plus federal assignments like the Base Realignment and Closure projects and it was his agency that came up with “Jack Hammer” for the national slow-down-for-highway-workers campaign. All of that required high level, insider, federal favor pay-back and I was digging for some subcontractor work out of him when he answers my unasked question:

“Yes, they know me at CIA. And Lagueruela is even better known in Cuba where there is a price on my head.”

So what do I say now, me the inebriated interviewer? The door is open and the next question is critical. I am searching through the fog of my intoxication but come up with nothing but another drink. Who ordered those?

Smoke rings glide from his lips as Andy laughs and continues on his own. “At one time, my friend, I get a call. This was just after the Missile Crisis. Do you know the Missile Crisis?”

“Of course.”

Apparently, he tells me, some CIA operatives had acquired a Soviet Officer’s parade uniform that would fit Andy—a rare find because Andy was beyond a 3X. The operatives were quite excited about his, as if this was “it”; the one thing that was certain to topple Fidel. Andy, of course was game. He was hustled out to New Mexico where, at a top secret federal facility, where he was trained in high-altitude parachuting. Now, just looking at Andy as he winds out this tale of espionage and intrigue, I can tell that he has always been more of a gourmet that an athletic-type and he must have gone about this specialized combat training with an odd combination of patriotism and dégagé. He was certain to die. Andy puffs himself up as he tells me about the jump: he was actually pushed out of a high-altitude AWAC. “I would have jumped on my own but I thought that it was just a moment too soon.” He wore an oxygen mask for the freefall part of the drop and a large wrist watch that told him when he reached the altitude where he was supposed to could pull his ripcord. It was his only parachute jump he ever attempted and the mission was a complete success: he landed close to where he was supposed to, on a plantation that used to be owned by a former brother-in-law. Contacts from Omega met him in the field; he was scurried off to a series of to a safe house, hiding in the jungle in a Soviet officers dress uniform, and eventually smuggled out of the country in a fishing boat, still dressed for a parade on Red Square. The mission was a complete success.

“What did you do? What was the mission?” I ask.

“Just that.” His cigar is well poised and he releases the smoke as if it was a sentence in our give-and-take. “I crept in. I crept out.” And when the blue smoke of the Nicaraguan tobacco from Cuban seed cleared a look of great disappointment filled his eyes and he spoke with a sarcastic inflection, “Another blow to the regime.”

“What’s the point?” My words managed to fall from my cotton-dry mouth.

Andy leans into me once again. If not for the tiny table between us he may have fallen into my lap. “This is how you American spend your money and,” he pushes a stubby finger into my face, “and this is the fate of my country.”

Andy manages to find his way to his feet: cigar still in hand as he lumbers off to find the bathroom. I snuff out my cigar in the ash tray, take an olive from the Martini glass and plop it in my mouth as my eyes slowly cast about the room. The Tango dancer in cherry-red has attracted a few more men to the bar. The junta of canasta players unabashedly lay their hard glances on me, perhaps as a warning, wondering if their chubby spy chief was reveling too much information and I realize with a sudden and hardy laugh that I am a background character in a black-and-white, B-movie.* * *

Andy returns refreshed and pulling two new cigars from the inside pocket of his wrinkled linen suit coat while a white jacketed waiter following him with two exquisite cocktail glasses on a tray. I had had enough but I would certainly have more. Andy fell into his seat, passed me one of his un-banded cigars and went to work on his with a silver sniper; carefully clipping a tiny piece off of the cap-end before sticking it in his mouth like a pop-cycle to moisten the head wrapper. I attempted to mimic his savoir faire and managed to get mine lit without causing a fire.

The action of smoking the cigar became an integral part of Andy’s dialog; he leaned back in his chair and drew in a long toke. “I have permission to return.” He paused, met my eyes and exhaled a veil of thin blue smoke. “But I am not certain that it will honored.”

“Cuba, you mean?” I exhaled in kind.

“They could easily pick me up at the airport and you, my friend, will never know how the story ends.”

I attempted to use my cigar as dialog, inhaling, leaning back and giving his a look that was mean to say “go on.”

“My mother’s older sister and her family are still in Havana, living in part of a house we once owned. The house has become run down. She shares it with others. They have electricity frequently enough but the old elevator hasn’t worked for, I don’t know how long. To get water to her bathroom on the third floor they have a garden hose dropped from her balcony to a spigot on the street. She is getting old and she has the last I have heard, the matching pistol.”

“Pistol?”

“One of two….”

Andy paused as if to consider . . . what? Martini or cigar? Whether or not he should tell me? Tell me what? Whatever it was I was eager for the next act in this B-movie so I chose the tact that had served me so well earlier in the evening: I remained silent. Aver a sip from his martini and a pull on his cigar Andy gave me a wry smile and I know that I would have it.

Andy told me that his great grandfather was the last Governor General of Cuba to be appointed by the Spanish Crown. He brought with him a deep swath of Spanish history and two hand-tooled dueling pistols that had been in his family since the Castilian period. They were the old mussel-loading kind that fired by a flintlock apparatus, the kind gentlemen in white wigs and white hosiery used to settle disputes before the days of Judge Judy.

Although a Court appointed autocrat Grandpa Lagueruela, Andy tells me, had had some degree of political savvy. This was the late ninetieth century when Spain was going through the long agonizing process of losing its Caribbean colonies one-by-one and it was Cuba’s turn to fall. In the ancient way of collapsing monarchs—a technique that had work so for Castilians in the sixteenth century, when those elegant pistols were made—Governor General Lagueruela married into an old Cuban Creole family expecting, Andy assumes, that such a union would mends some fences with the locals. That didn’t work out so well. Señora Laugueruela’s deeper sympathies lay with the more liberal causes and their oldest son was sent to Princeton University in the United States where he became sympathetic with the Mambises and, to scoot right to the end of a more complex journey, Andy’s grandpa ended up serving as an aide-de-camp to Teddy Roosevelt as he charged his Rough Riders up San Juan Hill to topple the Spanish.

“I have seen the letter that my grandfather received from his father, the Governor General. It is written in his very elegant hand on an oversized piece of parchment, more like a manifesto than a letter to his own son. My great grandfather had an exceptionally dramatic command of a beautiful language. The words themselves brought tears to my eyes.”

Andy is out of cigar and martini at this point and I with my two-toke cheroot smoldering in the ashtray and my cocktail glass either half-full or half-empty continue to hold up the silent side of our conversation with an encouraging nod.

“I paraphrase here, of course. I could never match the phrasing of the caudillo.” He nodded: we were locked eye-to-eye. “The letter told of his aspirations for his son and he spared no sentiment telling of his love.”

The letter accompanied one of the two dueling pistols complete with powder and shot. “Carry this with you at all times in the upcoming conflict,” the Governor General instructed his son, “as I will carry the other. When we cross paths, como vamos a, you must put a bullet straight through my heart—me mata muertos,” was the way that Andy recalled the wording, “and you must do this before I take your life, for I certainly will.”

I lean it to catch each of the word that fell from Andy’s lips. His voice begins to slur and his words are alternating too frequently between Spanish and English. The gin, it seemed, was getting the best of him as I was rapidly sobering in the resplendence of his compelling novella. Andy said something of the Governor General bearing the double burden of killing both a traitor to Spain and the bearing sin of killing his own son; therefore he expressed, according to Andy, a hoped that the son would dispatch him first.

Andy seems content to end his story with the end of the letter, or perhaps he is too wasted to continue so I speak up. “So, what happened? Did they cross paths?”

“Ah yes, the moment of angst came at the surrender, when it was time for the Governor General to surrender his sword to the armies of Cuban independence. My grandfather, still the aide-de-camp to the Americans, was in attendance.”

“With is dueling pistol?”

“Quite possibly. I don’t really know.” Andy pauses and takes a breath. I can see that this story has exhausted him. “The stories that are passed down on my side of the family tell of how the Governor General, having lost Cuba for his country and having a sworn pledge to fulfill, loaded his pistol with shot and power and placed in in the leather holder that he was going to wear to the surrender. Some of his staff testifies to this.”

Another long pause and Andy searched his memory.

“And? Did they meet?”

“No,” he said abruptly. “The old man suffered a fatal heart attack in his carriage on the way to the surrender ceremony.”

A dense uncertainty freezes for a long moment before Andy unleashed a loud and uncontrolled barrel laugh. I break into laughter with him, though not really knowing what was funny. Our laughter is loud and contagious enough for the conspirators at the canasta table to join in our laughter which captured the attention of the Tango group at the bar to turn and join in. For what? Nobody, not even me, knew where the humor lay except that we were drinking a laughing and some of that story may have been true.

* * *

Apparently the letter of the Governor General and one of the dueling pistols are now with the Lagueruelas in Miami. This would be the set that Andy was familiar with. The other pistol remains with the Lagueruelas who stayed in Cuba. Andy’s true mission is to reconnect with the family that he left behind in Cuba and the tale of the two pistols give him a colorful cause célèbre to justify his journey home.

I snagged the bill when it came. Andy held his hand out insisting that he pay.

“No, please. Andy. This is on me.”

He tried to pull the chit from my hand, we were both drunk and stumbly so the billet fell on to the table and stuck to a wet spot. Andy’s fat hand came down on top of mine as I tried to pick it up and we argued playful love which one of us would pay. I can’t remember which of us won but I do remember the two of us stumbling arm-in-arm down Navarro Street trying to remember where we had parked our cars.

140817 -2,685words

Andy Lagueruela did return to Havana in January 1998 and he was not arrested at the airport. Pope John Paul II was scheduled to make his historic visit to Cuba at the end of January and all foreign aliens were summarily required to vacate the island. So Andy was obliged to leave Cuba before he was able to catch up with the aunt who was alleged to have the patching dueling pistol.

Although the Spanish changed commanders on a rapid basis in their final years of mis-ruling Cuba, my cursory research could not find the name Lagueruelas in any of their rosters. The infamous Valeriano Weyler was the last to have the title Governor General a position he held from 1896 to 1897. He was replaced by Ramón Blanco who had the title Captain General of Cuba from 1897 to 1898. The Spanish got to surrender several times in the War of Cuban Independence. On July 17th 1998 it was a field general, José Toral, divisional commander of the Spanish IV Corp who surrendered Santiago to Joseph Wheeler and it was a dude named Adolfo Jiménez Castellanos with the title of Captain General in Havana who had the pleasure of formally surrendering all of Cuba to the Americans on January 1, 1899. No one had a heart attack on the way to the surrender ceremony.

Five Days With The Huaorani

Huaorani consider themselves to be the bravest people in the Amazon. Through uncountable millennia they have defended their piece of the Oriente rainforest by killing everyone and anyone who they come across who was not Huaorani. Their spears were left in the bodies of the trespassers to ensure that their message was clear. The great expanse of the Aztec civilization avoided them and the Spanish empire dared not encroach on their part of the Amazon. Not even The Liberator, Simon Bolivar, would take his indefatigable troops into the Huaorani’s small piece of Ecuador. Today they stand up against a foe that they know will destroy the rainforest and put an end to their way of life: Big Oil. At the time that I was born, no one in the world who knew how to read or write was even aware that the Huaorani existed. By the time that I die they will be extinct. That is why we had to go.

What struck me immediately was that the jungle is not the scary place I had imagined. It is the Garden of Eden—the most bio-diverse place on the planet. There was a plethora of insects but they were not swarming in your face all the time. You had to be ever vigilant for snakes, scorpions, and other dangers beneath your feet. If you stumbled on a trail you did not reach out for a branch to steady yourself; it may have toxic stickers or the dreaded Conga ants that could paralyze your entire arm with one painful bite. You just let yourself fall to the ground; or better yet, you learned to walk more thoughtfully down the jungle path. It was wet and muddy.

What struck me immediately was that the jungle is not the scary place I had imagined. It is the Garden of Eden—the most bio-diverse place on the planet. There was a plethora of insects but they were not swarming in your face all the time. You had to be ever vigilant for snakes, scorpions, and other dangers beneath your feet. If you stumbled on a trail you did not reach out for a branch to steady yourself; it may have toxic stickers or the dreaded Conga ants that could paralyze your entire arm with one painful bite. You just let yourself fall to the ground; or better yet, you learned to walk more thoughtfully down the jungle path. It was wet and muddy.

The humidity could reach 100% but we were shaded and never far from the cool, flowing waters of the Shiripuno River. The jungle, I learned, could create its own rain shower when the evaporation of moisture from the understory was trapped under the broadleaves of the higher canopy.

Fa’a Samoa

It is awfully difficult for a barefoot school boy to pay attention to his lessons with the Pacific Ocean pounding on the beach just beyond the playground of Mokapu Elementary School. Even with less than half of my attention in the classroom I do remember Miss Wahineaukai teaching us, in her Pigeon-English, about the first Polynesians to settled in the Hawai’ian islands such a long time ago. With no compass or maps, with no written tradition in their culture, they sailed into the tiny island chain—the most remote body of land in the planet—after months in open canoes. Luck, I imagined: like seeds blown from a dandelion, a few found fertile ground but most of them perished at sea. The words of that Miss Wahineaukai that stayed with me through my entire life were “the wayfinders who guided these boats were high priest who had been given the vision and talked to the Gods of the sea. All of the strong kanes who manned the paddles placed their absolute faith and obedience in the wayfinder.”

Yeah! I got that. The only way that I would get in an open canoe and paddle out into the endless ocean for months on end, where I was probably going to die, would be if I had a delusional faith in the man at the helm. These Polynesian dudes were crazy—or driven by something that I had yet to understand, something in the seductive call of the Pacific Ocean.

Samoa is the heartland of Polynesia. It was from the Samoan islands, just below the equator and half way between Honolulu and Auckland that the Polynesian people, “the most remarkable seafaring people in history”1, sailed forth to become the Māori of New Zealand, and the first human visitors to Easter Island. It was from Samoa that they migrated to Tahiti and from there on to Hawai’i. Growing up in those islands I came to view the Samoans as the hardcore Polynesians, they were the big guys in the toughest gangs in the schoolyard. They played the hardest: confusing sportsmanship with pain on the playing fields and in the lineup out on the breakers. I also remained enchanted by the great Pacific Ocean long into adulthood and could never shake my childhood impression that the Samoans were the only people to master that vast body of water, the single largest piece of the planet. There came a time when felt compelled to go to Samoa, slide into the heart of Polynesia and climb to the peak of Mt.’Alava where I could see the Pacific’s horizon 360degrees around me; to stand where the high chiefs of ancient Samoa stood and, for some reason, said to each other “lets sail out that way.” I wanted to drink their coolaid; feel whatever mystical pull that made them do it. So I went and what I found out changed my entire perspective, not only about how the Polynesian did it but of the white man’s way of recording history.

Samoa is the heartland of Polynesia. It was from the Samoan islands, just below the equator and half way between Honolulu and Auckland that the Polynesian people, “the most remarkable seafaring people in history”1, sailed forth to become the Māori of New Zealand, and the first human visitors to Easter Island. It was from Samoa that they migrated to Tahiti and from there on to Hawai’i. Growing up in those islands I came to view the Samoans as the hardcore Polynesians, they were the big guys in the toughest gangs in the schoolyard. They played the hardest: confusing sportsmanship with pain on the playing fields and in the lineup out on the breakers. I also remained enchanted by the great Pacific Ocean long into adulthood and could never shake my childhood impression that the Samoans were the only people to master that vast body of water, the single largest piece of the planet. There came a time when felt compelled to go to Samoa, slide into the heart of Polynesia and climb to the peak of Mt.’Alava where I could see the Pacific’s horizon 360degrees around me; to stand where the high chiefs of ancient Samoa stood and, for some reason, said to each other “lets sail out that way.” I wanted to drink their coolaid; feel whatever mystical pull that made them do it. So I went and what I found out changed my entire perspective, not only about how the Polynesian did it but of the white man’s way of recording history.

* * *

Like the big bang that created all of the cosmos no one really knows where the settlement of the Pacific really began but we are clear on where it ended. Ten thousand years ago the Lapita people left New Guinea2 or the Neolithic Hemudu shoved off of the China3 coast sailing forth against the prevailing winds and currents in open canoes, crude sails of woven pandanus and planking tied together with coconut rope4; no more than Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn had when they drifted down the Mississippi in the 1876. By 1,000 CE these seafarers had settled just about every inhabitable land mass in the 30million square miles of the Pacific Ocean5 that is now called the Polynesian Triangle. In the last phase of this Great Polynesian Migration, when they sailed from Samoa in fleets of up to 100 boats, loaded with chicken, pigs, extended families6 from where they would establish themselves on every inhabitable island in the central Pacific. The wayfinders who piloted these fleets obviously knew what they were doing. They could only provision their boats to survive 20 days at sea7so they would have to island hop their way across the vast ocean. Much of Polynesian folklore is built around the mystical powers of the wayfinders, as Miss Wahineaukai had taught us in fifth grade, but in fact the Great Polynesian Migration owes its safety and success to learn skills and solid science. The critical measurement of successful navigation, points out Jack Lagan, a contemporary navigator instructor, lies not in the discovery of new islands in the middle of the ocean, “rather in the ability to find them agian.”8 Captain James Cook demonstrated that to the literate world in the late 1770’s. The Polynesian had mastered that skill some 800 years before that.

When Cook first “discovered” Tahiti in 1769 he took onboard a “priest” named from Tupaia who was from the distant island of Ratata9—confusing, once again, the spiritual title of high priest with the role of wayfinder, which is what he was. Without referring to instruments or charts, Tupaia guided Cook 300nm south to the tiny Polynesian island of Rurta. As sort of a parlor game some of Cooks officers sketched out a chart as Tupaia described the South Pacific from memory, creating what they called “Tupaia’s cranial map.”10 Tupaia didn’t just know the he names of 70 separate island groups through the Polynesian Triangle “he knew where they were and how to get to them.” You can see Tupaia’s chart today in the Manuscript Collection of the British Library in London 11 and you can see just how accurately it lays out the tiny islands throughout the Pacific. If you were a Polynesian you wouldn’t need a map top find your way around the Pacific—you’d know how to get where you were going without it.

So how did they do it? How did they cross 3,000nm of ocean in open canoes reliably returning to their home island then sailing off again like trains out of Grand Central Station. They had no charts, no compass, no chronometer, no sextant, no GPS, and no written tradition to pass information down to succeeding generations. The “fundamental elements of the Polynesian world: water, waves, clouds, stars, sun, moon, birds, fish and water itself. Bring to that the raw power of empirical observation, of universal human inquiry. The skills of the [Polynesian wayfinder] are not unlike those of a scientist.”12 Star paths are quite reliable but not always visible. The wayfinders did not perceive themselves as moving towards a point on a chart. Rather they saw their boat as a fixed point with “distant islands moving towards the navigator.”13 The most reliable constant in the open sea are the trade winds and the swells. If you can learn to distinguish the feel of the prevailing breezes from the constant trade winds and if you can teach yourself to senses the difference between the surface waves and the pull of the deeper current you could find your way reliably to places that were thousands of miles away from each other. Polynesian wayfinders were known to lay in the deck of their twin-hulled wakas for long periods[citation needed] so they could cognate the rhythmic expanding and contracting of the water pressures. A sailor at the helm could then, and can now, reliably keep a boat on course for days by keeping the primary swell pushing consistently against the boats port quarter* Long before an island is visible the keen wayfinder can feel the reflected swell pushing off of the land mass and, similarly there is no metaphysical spirit involved when they sense a refracted swell, the back wash of a land mass they are sailing past.

Then there are the clouds and/or fog that form when the moist air over the sea rises when it blows into the solid mass of an island; and the birds. All seafaring people know that large Frigate Birds feed far out to sea, up to 70mn from land and smaller birds like the Brown Noddy can’t make it more than 20mn offshore.14 The smaller the bird the shorter the shorter the feeding range therefore the closer to land you must be. Crossing the Pacific in an open canoe is a daunting challenge, but, like a mountain climber that can see the peak overhead, the Polynesians did not have a problem knowing where they were or where they were going. That was a matter of staying tuned into the natural elements of their world.

* * *

In yacht clubs and bars overlooking the Pacific today the great debate among sailors, the folks who cross the waters in under sail, is between the old salts who rely on traditional navigation (using sextants, compass, and chronometers) who look despairingly on the young skippers who can’t find their next port without a GPS device. “That’s not sailing,” I hear the old salts complain. “What would they do if their electricity goes out?”

Well, the GPS skippers could do the same thing that the old salts could do when they drop their sextants on the deck, is my answer. They could stick their head out of the companionway and take a look at the world that they are sailing through.

As is should be, the fear of being lost as sea has long been the great deterrent to ocean cruising, and the advent of GPS navigation has changed that significantly. There are twice as many blue water sailing passages being made today than there were in 2006.“In all the planet’s seas, at any given time, there are about 10,000 cruising boats taking long-term transoceanic voyages.”15 Navigation skills once acquired by the manipulation of esoteric contraptions (like the sextant) and classroom certification are easily replaced with idiot-proof technology: “a GPS trumps a sextant . . . and an iPad makes a fantastic chart plotter.”16 Personally I find this debate rather moot, at best an amusing drinking conversation. Both the old and new navigation technologies serve to distance us from the natural world that we seek. “The history of navigation is the history pursuit of accuracy.”17 Jack Logan reminds us and from that perspective it is a matter of putting dots on the map with greater precision. But there is much more to it. Dr. Tianlog Jiao, anthropologist with Honolulu’s Bishop Museum, takes a much grander view of ocean navigation: “The whole story is about migration, but it’s also about diversity, struggle and resilience. It’s about understanding one’s ancestral roots . . . and at the same time realizing that we are all connected.” 18 Wow, and I thought that I was just trying not to get lost out there.